Hope and Despair: What does it mean to hope?

Losing hope, or falling into despair, on the spiritual path is a deeply painful and penetrative experience. What does it mean to hope for something? To hope in one sense means to trust, or have faith, in something. It also signifies an intention to do or accomplish something, and a longing to achieve or obtain a thing. I have often heard the phrase, “to be beyond hope and fear,” within the Buddhist tradition. I have an intuitive idea of what that means, and yet I also see that I very much hang on to hope as a driving force of my practice. Perhaps the most obvious way this shows up is in the desire for spiritual awakening. Without that desire why would any of us do this practice every day for so many years? Our reasons for wanting spiritual awakening may differ, and still, it is essentially what we are initially striving for.

When Obstacles Arise

With that hope, though, comes the realization of obstacles. Inner obstacles: the mind’s five poisons. And outer obstacles: work, family, and our basic survival needs. When these obstacles appear too great, such as habitual patterns of sadness and anger, depression and anxiety, or we get weighed down by the overwhelming daily demands of work and parenthood, then our hope can quickly turn into despair. Furthermore, when we discover that meditation does not magically resolve these obstacles for us, then we can mistakenly believe that we are either doing the practice wrong and must push ourselves harder, or that there is something fundamentally wrong with ourselves that simply make us bad candidates for enlightenment.

Jack Engler sums up well the struggle or tension between where we find ourselves currently and where we hope to get to on the spiritual path: “Problems in love and work, and issues around trust and intimacy in relationships in particular, can’t be resolved simply by watching the moment-to-moment flow of thoughts, feelings, and sensations in the mind.” It seems to me that western students often separate a spiritual self from the psychological self, and think that by focusing on the spiritual self then the psychological self will naturally become purified without having to really roll up our sleeves and work on our problems. Engler goes on to flesh this out for us:

“The wish that spiritual practice could, by itself, prove a panacea for all mental suffering is widespread and certainly understandable. But it unfortunately prevents teachers and students from making use of other resources. And worse, students are sometimes led to believe by their teachers or their own superego that if they encounter difficulties, it’s because they haven’t practiced long enough or haven’t been practicing correctly or wholeheartedly. The message too often is that the problem is in the quality of the student’s practice rather than in the mistaken assumption that practice should cure all. This leads to needless self-accusation and guilt, compounding how bad they already feel.”

Hope and Despair: You’re Not the Only One

Does this feel familiar to anyone else? This has certainly been the case for me, at times, and is no doubt the result of my own superego admonishing me. In fact, it has not only shown up for me personally, but it has also shown up in my work as a therapist.

I have seen what appears to be infinite variations of psychological suffering in those that show up at my door for help. I recall thinking, as I was listening to one of my clients discussing their pain and difficulties, that if only they could realize the fundamentally empty nature of the self then all of their problems would resolve, and they wouldn’t need me anymore. Couldn’t it just be that simple? Maybe all they need is a magnifying glass: some method of looking right into the core and seeing that the self doesn’t exist and then, poof! All their problems would disappear.

Unfortunately, it isn’t nearly that easy. It’s not simply a matter of seeing through the illusion of the self, nor is it about watching the moment-to-moment arising and passing away of experience or even having profound realizations in our practice. If this were the case, then we wouldn’t see conflict, disharmony or any type of scandal in Buddhist sanghas.

The Buddhist Path Is Like Long-distance Running

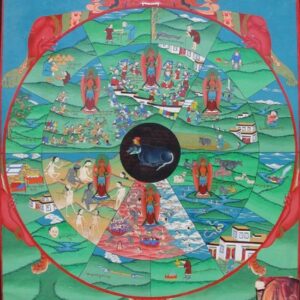

The Buddhist path is incredibly complex – beautifully so – interweaving a multitude of components the way a great weaver threads thousands of strands of yarn to build a blanket. In somewhat of a contrast to this complexity, the Vajrayana path holds the promise that enlightenment can be achieved in a single lifetime. Do I believe this is possible? Absolutely. However, when I position this as a goalpost for myself it becomes overwhelming and even painfully daunting. In my work with myself and in my work with others, I must take the path one small bite at a time and in so doing forget the goal. It’s kind of like long-distance running. When I set out to run a 10k, if I am thinking about the finish line the entire time, then it will be a long, miserable run and I will probably give up before I get there. I have to let go into the moment and be just where I am, working with each individual ache that comes up in my body and mind, and falling naturally into my pace however slow or fast it may be that day.

Hope and Despair: Embracing our Humanness

Our humanness is a radically complex thing. We cannot overlook our individual histories, or the convoluted and challenging relationships between ourselves and others (show me one person who has a straightforward and easy relationship with their family members). All of these aspects of our lives are the conditions in which we are showing up right now. It is the very essence of our current appearance as selves. The most compassionate element is that these pieces of our selves are not permanent or unchanging. We can improve! However, we must do the psychological work along with the spiritual work, otherwise we will despair at the gap between the two or worse – become blind to it and fool ourselves into believing we are enlightened.

Additional Resources

In this blog, Jamie discusses the importance of not separating the spiritual and mundane as we walk the Buddhist path. Phakchok Rinpoche often emphasizes a holistic approach and how important it is to keep balance in our lives. You may find it helpful to review this teaching about balancing practice and life in our previous blog. https://samyeinstitute.org/philosophy/balancing-dharma-and-life/

Note: This advice is not meant to take the place of mental health professional guidance. Mental conditions are complex and people differ widely in their conditions and responses. If you suffer from serious anxiety or depression, we suggest that you seek the services of a trained mental health professional.

Responses