I remember the day my then-two-year-old came busting through the door of my home office, where I had my meditation shrine and cushion set up and was attempting to practice. I was immediately irritated, getting up from my cushion to sweep my daughter up into my arms and carry her downstairs to her father. I then returned to my office closing and locking the door behind me. I settled back down onto my cushion, recentering my attention on my breathing. Within a few more minutes, my very persistent toddler was back at my office door only this time she was hitting it with her tiny hands and crying “momma!”

For a long time, I tried desperately and failed miserably to keep my meditation life and my family life separate. I struggled (and likely still to do some capacity) with the desire for achievement in my practice. It would be impossible, I imagined, to get into deep states of concentration with my children milling about at my feet. I needed them out of the room and totally quiet. Better yet—if my husband could take them out of the house altogether while I meditated that would be ideal! As most practitioners who are also parents well know, these kinds of hopes are unrealistic and unfair—not only to our partners, but also to our children.

We often read or hear about the importance of taking our formal practice into our daily life. Sitting meditation is where we train our minds, but daily life is where we put it all into practice. I had heard this often repeated, but until a few years ago I hadn’t actually applied it to the realities of parenting and the householder life.

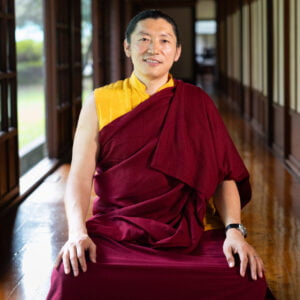

I have a vague memory of bringing this challenge up to Rinpoche-la during retreat a few years ago. I was complaining (probably even whining) about the difficulties of not having time to practice because either my children needed me, or else I was too exhausted by the time they finally fell asleep to muster the energy for concentration practice. Rinpoche had addressed the issue with ease and a bit of humor, it seemed. I recall him suggesting that I simply let my children into the room where I was meditating if that is what they wanted. This memory of his skillful advice seems vague to me now as I likely had reacted with resistance to it, thinking to myself that while his suggestion was a good one, it would still get in the way of my very goal-oriented practice.

I would wager to bet that most readers at this point listening to my journey are smiling, perhaps even chuckling to themselves, as the errors in my thinking were many. Yet they are common, and natural for many of us. Goal-oriented practice will only create obstacles and burnout. Trying to separate parenthood from spiritual practice will lead to spiritual bypassing, and ultimately, disappointment in one’s lack of progress in the cultivation of good qualities. Whether I wanted to admit it or not—parenting was my practice. It had to become my practice; these sweet babies were not going to leave me alone and I was not going to magically wake up one day in a nunnery with countless hours at my disposal for formal meditation practice. This was it—my whole messy life: soggy cereal, temper tantrums and bedtime meltdowns, lost patience, lost tempers, and sleepless nights.

Trying to separate parenthood from spiritual practice will lead to spiritual bypassing, and ultimately, disappointment in one’s lack of progress in the cultivation of good qualities.

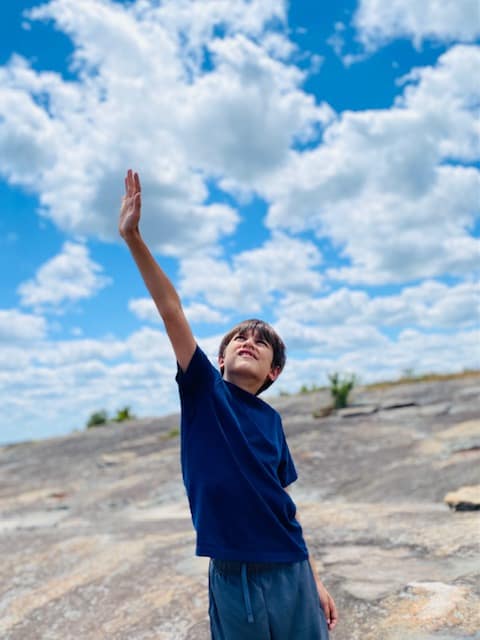

Although I had resistance to Rinpoche’s pith advice at first, the day would come when I finally gave in to it. I stopped locking the door. My children toddled into the room with wide, curious eyes. They asked what I was doing, I said “trying to calm my mind.” They asked to do it with me, so I set them up with cushions. They sat for a moment or two, then got up and wandered around the room some more. They picked up my ritual objects, observed them, and put them down. They sat in my lap and kissed my face. Then they left, off to play with their toys or run around in the backyard. And I was left with a quiet room, a peaceful heart, and time to practice.

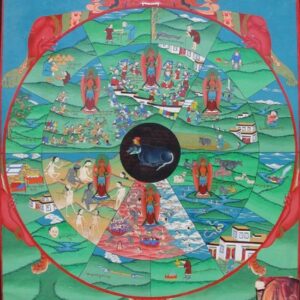

It took some contemplation and the willingness to be open to the circumstances of my life for me to learn that parenthood is one of the most rewarding paths of spiritual practice. It is hard—no doubt about it. You will come face-to-face with the ugliest parts of your shadow self. I once heard someone say that the difference between having children and not having children, is that those without children are able to keep on living in the illusion that they are pretty good people. Parenthood brings up all of the muck: our anger, our rage, our addictions, our clinging and attachments, our lack of emotional regulation, our resistance to the realities of impermanence, illusions of our own ability to control things. If we bring the spiritual path onto the path of parenthood, we have one of the greatest opportunities for constant practice available to us in this life.

Today, my daughter is five and she takes so much joy in hunting flowers for the altar and putting together her own small food offering. I find tiny plates made up with her favorite cereal, special stones and dandelions laid out on the shelf that I’ve given her in our meditation room. They peek their curious eyes into the camera of zoom retreats and teachings, and rejoice every time I bring a tsok offering down to the kitchen for indulging. Let your children into your practice. Invite their curiosity. When they test or trigger your negative emotions, bring mindfulness to the moment, be compassionate to yourself and explore what is skillful and unskillful. Parenthood has the power to become a tremendously fertile ground for our practice.

Responses

I love reading this and it sure inspire me to keep on going!

Thank you for sharing this.

warmly,

A 1-son mom