Ashoka became the third emperor of the Maurya Empire from c. 268 to 232 BCE. This unified empire encompassed a large part of the Indian subcontinent, stretching from modern Afghanistan in the west to present-day Bangladesh in the east, with its capital at Pataliputra. Ashoka was the son of king Bindusara and a grandson of the dynasty’s founder Chandragupta. While a prince, he served as the governor of Ujjain in central India. According to some later Buddhist legends, he also suppressed a revolt in Takshashila as a prince, and then upon his father’s death, killed his brothers to ascend the throne.

The name Ashoka literally translates as “without sorrow”. According to the Ashokavadana legend, his mother gave him this name because his birth removed her sorrows. He is also referred to in the Sri Lanka Dipavamsa by the name Priyadasi, meaning “he who regards amiably”, or “of gracious demeanor” and this may have been an official title. Ashoka’s inscriptions refer to him by the title Devanampiya (Sanskrit: Devanampriya, “Beloved of the Gods”). Several inscriptions clearly indicate the identification of Devanampiya and Ashoka as the same person.

Scholarly knowledge of Ashoka comes from his edicts and pillar inscriptions erected throughout his empire. Many of these are written in Brahmi script and are then translated into local dialects. These edicts are among the earliest long inscriptions of ancient India.

Ashoka’s Edicts

Ashoka’s edicts state that during his eighth regnal year (c. 260 BCE), he conquered the historical region of Kalinga in a particularly brutal war. His edicts record that the human and animal life sacrificed and the devastation of this war convinced him to take up a new policy of non-violence. Interestingly, these details are not found in the Kalinga region, and scholars interpret this omission differently. Ashoka recorded his commitment to the “dhamma” or righteous conduct, and again, interpretations vary as to whether this meant specifically the Buddhadharma or a more general policy.

Buddhist Sources on Ashoka

Buddhist legends about Ashoka exist in numerous languages, including Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, Chinese, Burmese, Sinhala, Thai, Lao, and Khotanese. These legends can be traced to two primary source traditions. These are:

- North Indian tradition in Sanskrit and translated into Chinese. These rely heavily on the Ashokavadana text from the Divyavadana as well as Chinese sources such as A-yü wang chuan and A-yü wang ching.1Strong, John S. (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Southern tradition, or the Sri Lankan tradition preserved in Pali-language historical-religious chronicles including the Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Vamsatthapakasini, and in Buddhaghosha’s commentary on the Vinaya, and the Samanta-pasadika.

There are several significant differences between the two textual traditions. The Sri Lankan tradition emphasizes Ashoka’s role in convening the Third Buddhist council, and his dispatch of several missionaries to distant regions, including his son Mahinda to Sri Lanka. The North Indian tradition does not elaborate on these but adds other episodes. Scholars differ in interpretation, but the intended audiences may account for some of the disparities.

Ashoka and the Bodhi Tree

Both the northern Ashokavadana and the Sri Lankan Mahavamsa include an account of how Ashoka’s jealous queen Tishyarakshita attempted to destroy the bodhi tree under which the Buddha became enlightened. In the Ashokavadana, the queen realizes her error in mistaking the tree for a female lover of the king, and she arranges to heal the tree. In the Mahavamsa, she permanently destroys the tree, but this version of the legend calls attention to the fact that a branch of the tree had been transplanted in Sri Lanka.

Ashoka and Buddha Relics

Both texts describe Ashoka’s unsuccessful attempts to collect a relic of the Buddha from the Ramagrama stupa. In the Ashokavadana, he is unable to match the devotion of the Nagas who guard the relic and fails at his attempt. In the Mahavamsa, his failure is explained because the Buddha had already predicted the relic to be enshrined by King Dutthagamani of Sri Lanka.2Strong, John S. (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass. Scholars point out that the Mahavamsa chronicle promotes Sri Lanka as the new guardian and home of Buddhism.

Both northern and southern traditions credit Ashoka with the building of 84,000 stupas or viharas. According to the Ashokavadana, he erected a stupa in every city of more than 100,000 throughout his empire. Within these, he encased Buddha relics in opulent caskets made of gold, silver, and other precious substances. His activity in marking the location of key events in the life of the Buddha, as well as building stupas to honor and protect the relics of the Buddha, is celebrated throughout the Buddhist world. Subsequent rulers in Buddhist kingdoms look back to the legends of Ashoka in their erection of temples and monasteries, depicting him as the most celebrated royal patron. The Mahavamsa states that Ashoka ordered the construction of 84,000 viharas (monasteries) rather than the stupas to house the relics.

Ashokan Inscriptions

There are over 30 inscribed extant pillars attributed to Ashoka as well as carved edicts on boulders and cave walls, issued during his reign. These pillars have been found throughout modern Pakistan and India, and a number of them mark important Buddhist sites. The Chinese pilgrims to India commented on other pillars which no longer are found at their original sites, but the Ashokavadana tradition describes the emperor visiting the key Buddhist sites under the tutelage of the arhat Upagupta.

In 1896, a stone pillar in the Rupandehi district of Lumbini was discovered. The Brahmi inscription on the pillar states that Ashoka visited the site in the 3rd century BCE and identified it as the birthplace of the Buddha. The translation of the edict reads:

When King Devanampriya Priyadarsin had been anointed twenty years, he came himself and worshipped (this spot) because the Buddha Shakyamuni was born here. (He) both caused to be made a stone bearing a horse (?) and caused a stone pillar to be set up, (in order to show) that the Blessed One was born here. (He) made the village of Lumbini free of taxes, and paying (only) an eighth share.

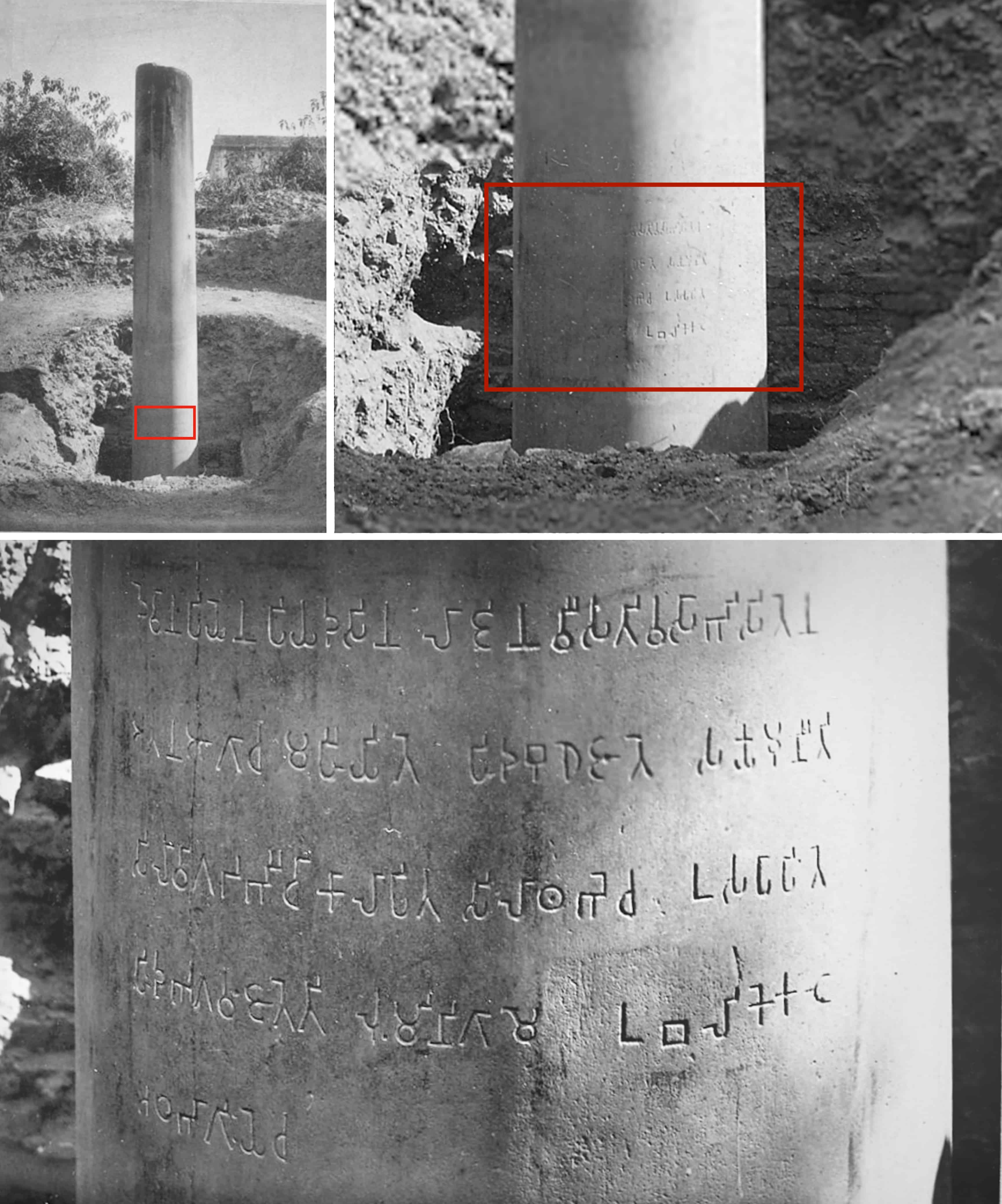

In addition to this inscription, another Ashoka pillar is found nearby at Nigali Sagar, in modern Nepal. This pillar relates the visit of the emperor to the stupa of the second buddha of this era, Kanakamuni (Pali Koṇāgamana). The inscription is said to date to c. 249 BCE and records his visit as well as the enlargement of a stupa dedicated to the buddha, and the erection of a pillar:

His Majesty King Priyadarsin in the 14th year of his reign enlarged for the second time the stupa of the Buddha Kanakamuni and in the 20th year of his reign, having come in person, paid reverence and set up a stone pillar.