A Big Surprise

I work in a public research university the size of a small city, with its own power plant and water supply systems, with over 41,000 students, and 5700 faculty members. This past fall, as advisor to a student meditation club, both I and the students were startled when at the beginning of the semester, they had signed up not the usual dozen or two, but over four hundred students interested in meditation! Of course, to put that in perspective, it’s actually only around 1% of our university community as a whole. Still, the numbers surprised us all.

Anxiety on Campuses

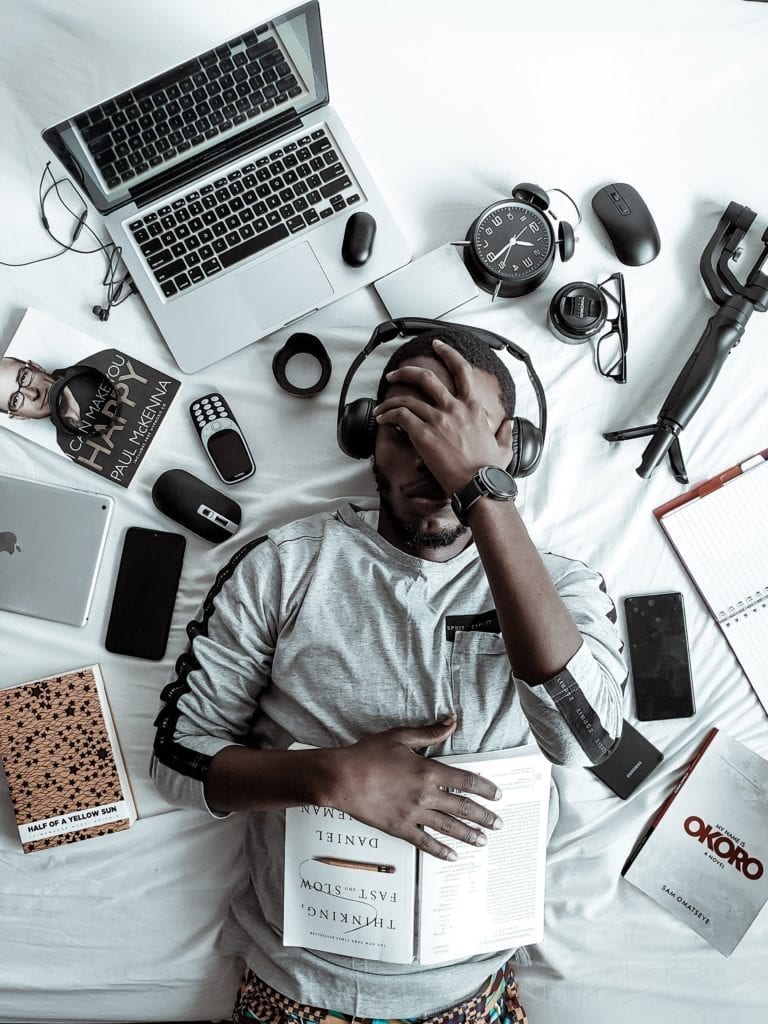

We can see why there is such interest. The statistics on anxiety, depression, and other types of psychological suffering among contemporary college students show there are significant issues. Anxiety is widely reported to be the number one psychological challenge among students today, and in a recent survey, 97% of students reported technological distractions are a problem both inside and beyond the classroom. Any faculty member can confirm this: to give a single anecdote, I was sitting at one of our public events behind a young woman who had brought her laptop, and she had nine live social media feeds open at once in just one app. More in others. Did she hear anything at the event where she was sitting? It seems unlikely. Many students find themselves in a constant state of distraction.

Might Technology and Social Media Play a Role?

Why is this happening? What are some causes for the dramatic statistical increases on campus in anxiety, depression, even suicide? This past fall, the students and I hosted several meditation workshops, and at the first one, we had a public conversation about those questions. Students were convinced that technology and social media played a major role in all of the psychological issues mentioned. But they found it difficult, if not impossible, to conceive of controlling either one.

A recent study (Cigna, 2020) confirms students’ suspicion of tech and social media with some perhaps surprising numbers. In addition to a rise in other psychological stress conditions, there has been a dramatic rise in reported loneliness, and nearly three quarters of heavy social media users were classified as lonely in the study, while 52% of light social media users were. 81% of “Gen Z” workers reported being lonely at work, and 69% of “millennials.” What to do?

An Experiment

In the workshop, the students agreed to an experiment: in addition to practicing a short shamatha meditation each day or as often as they could, they’d start to control their phones. I asked them how many slept with their phones, and nearly every hand in the room went up (perhaps every one—it’s possible). So they (or at least some) agreed to put their phones in another room at night. Later in the semester, I asked them how it went, and many of them said they’d felt better and slept better with their phones elsewhere. One student raised his hand and said that while he wasn’t able to give up his phone at night, he had made progress: he wasn’t sleeping with his laptop anymore.

We Live in a Shared Context

Those engaged in long-term practice are well aware of the larger social and cultural context in which not only these university students, but all of us are living. What the students are reporting, what is visible in the national statistics, reflects our collective set of challenges. When you have the opportunity to share some advice or practices for stabilizing the mind, it’s helpful to bear in mind the shared environment of constant technological distraction and all the emotional upheaval or kleshas that arise from invidious social media comparisons, from the sense that others have it better, that “I” don’t measure up. We live in a shared context, and just bringing that gently into people’s awareness can help to begin to relieve some suffering.

In the workshops, we engaged in the secular practices that Phakchok Rinpoche has taught over the years, as well as the ones he and Erric Solomon shared both in public events and talks, and in their book Radically Happy: A User’s Guide to the Mind. Students responded well to them, in particular to shamatha by using the breath as a focus, but to others as well. They have continued to meet, and they continue to meditate on a regular basis. And they have started to manage the phones and tech in their lives with more awareness and, they report, that’s important and helpful too.

Moving It On-Line–Teaching and Practice in the time of Quarantines

This spring, during the novel coronavirus contagion and various quarantines, after students were dispersed and remote teaching was underway, our group also met online. Here are two practices that students said were particularly helpful–and that might prove to be helpful to you also.

Breath Awareness Practice

The first is to become centered by focusing on being aware of the breath. You may encounter numerous variations of this mindfulness of breath practice, but in essence, they all touch on the same key points.

- Turn your attention gently to your breath.

- Become aware of the in-breath, the pause, and the out-breath.

- Maintain this awareness by counting slow exhalations, one, two, and continuing until our meditation period of ten or fifteen minutes ends with the ring of a small gong. (You can set a timer or alarm for yourself.)

- If you forget, or get distracted, just bring your mind back and start over—no worries!

“Resting in the Light of Kindness” Practice

The second is what Phakchok Rinpoche and Erric Solomon, in their book Radically Happy, call “Resting in the Light of Kindness,” in which you recognize and rest your attention on all the kindness and shared joy that you’ve experienced or observed and that sustains all life in every direction. As you participate in this fundamental kindness, the immediate challenges we face lose their hold on us, and anxiety and distraction fade away. Their instructions are as follows: (1)

- In your morning meditation, start by creating space.

- Imagine the people who have offered you kindness or care as part of a chain or web that goes on and on–the carers of the carers, almost into infinity. It’s an unending lattice of support–kindness and care and gratitude and appreciation.

- You can imagine everyone as bathed in the warm light of loving joy, all these people interconnected by kindness. Imagine not only what it looks like but also how it feels.

- Recognize that although you have suffered setbacks and trauma in your life, you are here because of kindness and care.

- Then rest for a few minutes by focusing again on your breath.

Coming back to these foundational practices, students affirmed, helps us stay centered and be more present to others and more helpful, less anxious, and more aware. After all, we’re all in this together.

Further Reading

For another look at anxiety, see the blog Anxiety: Seeing Through the Spin.

For further reading on how to confront and manage distractions, see Distraction: Tools to Avoid the Daze

And for more on beginning a meditation practice: Cultivating New Habits for Busy Minds and Mental Maintenance Creates Stability.

(1) Phakchok Rinpoche and Erric Solomon Radically Happy: A User’s Guide to the Mind (Shambhala 2018), p. 133

Responses