Societal Human Values Series # 6

Tibetan Emperor Songtsen Gampo, (Srong-brtsan-sgam-po), reigned 629-650 CE. Among his many achievements, he promoted a moral code known as the Sixteen Principles of Societal Human Values (mi chos gtsang ma bcu drug). As the Dalai Lama’s translator, Thupten Jingpa writes, “Most of these sixteen values have to do with promoting greater societal well-being and living one’s life with dignity, honesty, and respect for others.”

Phakchok Rinpoche frequently emphasizes the importance of living respectfully in society. He encourages students to memorize and internalize these points of conduct as a core foundation for our practice of the Dharma. If we don’t hold this moral code well, then whatever higher practices we engage in will be unlikely to bear much fruit.

This is the sixth in a series of explanations of these sixteen principles. The majority of this post was written before the global, Covid-19 pandemic so obviously many of the examples cited won’t be fully relevant again until there’s a return to more normal, pre-pandemic social interactions. Nevertheless, while the specifics may need to change in the short term, the principle is perhaps more relevant now than ever before. In this time of social unrest and global health crisis, people need one another more than ever. Finding ways to express that care may be more challenging than before, but as the need increases, so too must the bodhisattva’s resolve.

Principle #6 Being benevolent to your neighbors and countrymen (yül mi khyim tsé la pen dak pa)

We could also translate this instruction as simply “help” or “benefit” your neighbors. The Tibetan verbal phrase phan gdags pa translates the Sanskrit term anugraha, which connotes “to do a favor”, or “to show kindness.”

Be nice to your neighbors! If we recall that these principles are meant to ensure social harmony, this value is easy to understand. When we live with others, we all benefit if we take care of each other. Throughout history, humans have bonded together in family and tribal groups where shared resources and skills made daily life more sustainable. Benefiting our neighbors continues this natural human inclination in the modern era.

Lots of Neighbors, But Lack of Connection

According to recent studies, humans are now packed into dense clusters at a higher rate than ever in history. As Hannah Ritchie notes, “More than half of the world’s population now live in urban areas — increasingly in highly-dense cities.”1Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2020) – “Urbanization”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization And this trend is continuing to grow. As information from the UN indicates, “By 2050, global population is projected to increase to around 9.8 billion. It’s estimated that more than twice as many people in the world will be living in urban (6.7 billion) than in rural settings (3.1 billion).”2Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2020) – “Urbanization”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization

Loneliness and Vulnerability

Such statistical data would lead us to believe that we should be interacting with our neighbors more than ever before. But, surprisingly, studies also indicate that loneliness is on the increase. Those who study population shifts also inform us that vulnerable population groups, such as the poor and the elderly, and those with physical disabilities, often suffer from social isolation due to poor urban planning. As people age, they may find it more difficult to navigate dense urban spaces and then find themselves alone and cut-off from social interaction.

When societal mobility increases, people often lose connections with their social networks. When a person settles in a new environment it takes time and effort to forge new connections. Studies show that as we age, we tend to meet fewer people, and “the number of close friends we have peaks in our 20s and then steadily declines.”3Denise Cummins, Ph.D., https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/good-thinking/201502/why-you-might-find-it-harder-make-new-friends

And in busy urban settings or when one is adjusting to a new life, making friends may be harder to do than one expects. In smaller towns, or in previous generations, family members tended to live closer together and larger circles of support were common. Neighbors knew each other for longer periods and therefore tended to care for each other when necessary. While modern life presents special challenges, we can expand our connections with others.

During the global health crisis, loneliness and vulnerability may be even more pressing concerns.

Getting to Know Your Neighbors

When we read the advice to be kind to our neighbors, we can reflect on our own situation. Have we taken the time to meet those who live on our floor, in our apartment building, or within a few blocks? Forging connection with your neighbors is like any other habit; it becomes easier if we break it down into small pieces and repeat it frequently. Even while social distancing, we can still find creative ways to make those connections.

Start by making the first effort. Too often, we miss opportunities to forge connections out of self-consciousness or fear. But it doesn’t hurt to “make the first move” and we may be pleasantly surprised. We can practice smiling (even behind a mask, it will show in the eyes), waving, and greeting people kindly when we pass them in the hallways or wait for the elevator. Obviously, it helps to observe cultural particularities, so be attuned to how others act; few people reject courtesy and kindness.

Helping Your Neighbors

Now that you’ve taken the first steps and met the neighbors, try to really see them. Ash how they’re doing? How they’re handling the current challenge? Perhaps your neighbor is elderly or immune-compromised. Maybe you can go grocery shopping for him or her and then drop off the groceries at their door. Something as simple as that might both foster connection and protect their health.

Or if you notice that your neighbor is leaving on a trip, why not offer to water plants? Or ask if there is anything you can do to help him or her out. People often are shy about asking for help, or are afraid to bother others. But especially now, many need help, and you might be surprised to see how welcome your offer of assistance is.

Pass on Local Knowledge

If you see new people moving into your neighborhood, take a few minutes to introduce yourself and offer a few comments about the area. Suggest a favorite restaurant or coffee shop, or ask if they need any help finding service businesses in the area. Maybe they need help finding a testing center or a grocery store that isn’t out of yeast. When people move, they often find new areas a bit overwhelming, so if you can make a few suggestions they can relax a bit and feel more comfortable. This goes for long-time neighbors as well. Right now, when there are shortages, people often need advice or guidance on where they can find the essentials they’re looking for.

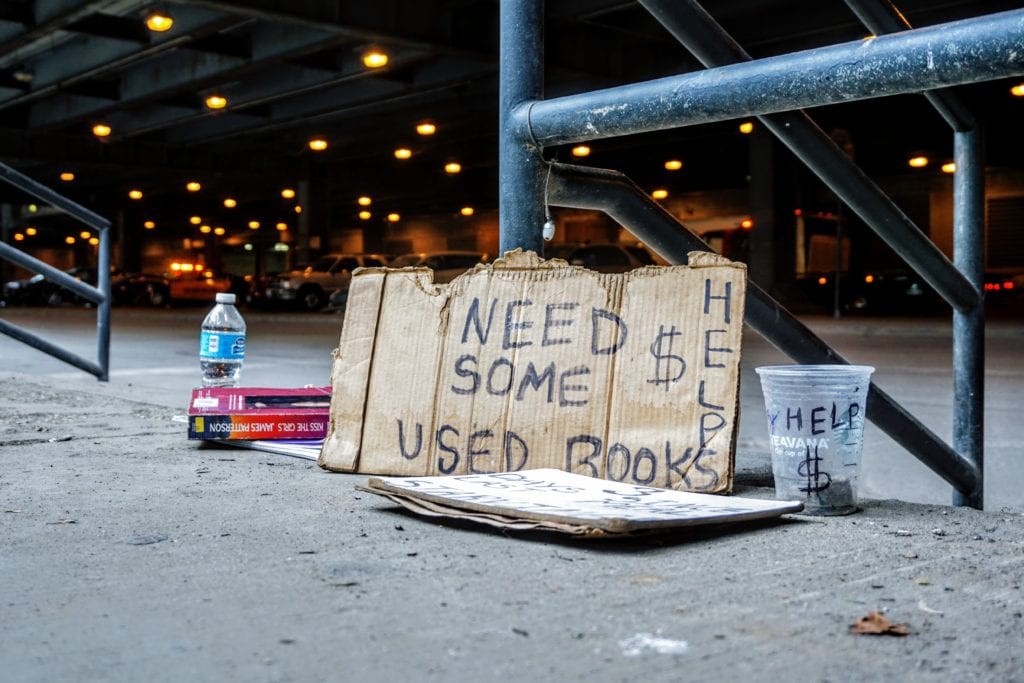

Kindness to the Vulnerable

We should be particularly conscious of those neighbors who may be the most vulnerable. When you take the time to notice others you may become more aware of their small sufferings. And if you step forward to ease their burden, whether through kind speech, physical actions, or simply the gift of time (a socially distanced conversation can be quite meaningful), you become a kind neighbor.

Avoid Transactional Neighborliness

We always need to pay attention to our intention. When we resolve to benefit our neighbors, we must avoid any thought that if we help them we will get something in return. Kindness and neighborliness should not become transactional, because then it is not genuine. Don’t expect praise or even thanks—we should be good neighbors simply because it serves others and alleviates suffering.

Exercises for Daily Living

In the next month, take a moment each day—preferably in the morning—to set the intention to be a kind neighbor. Then, as you leave your apartment or house, actively observe your environment. Whom do you encounter? What might you do differently to benefit those beings you see? And when you stop and notice your neighbors, can you think of them throughout the day and wish them well?

It helps to keep a journal when you begin a small habit change like this. Every day, note down something about the people you see, and also think concretely about how you might change your pattern of interacting with them.

Take tiny steps—maybe you hold the elevator door for a neighbor who carries a lot of packages—or you let someone with only one item go before you in line at the corner shop. But each one of these actions strengthens your neighborly muscles—and that’s how we change. And when we change, we may observe changes in how others behave as well. See if you begin to notice those changes—and rejoice!

Responses